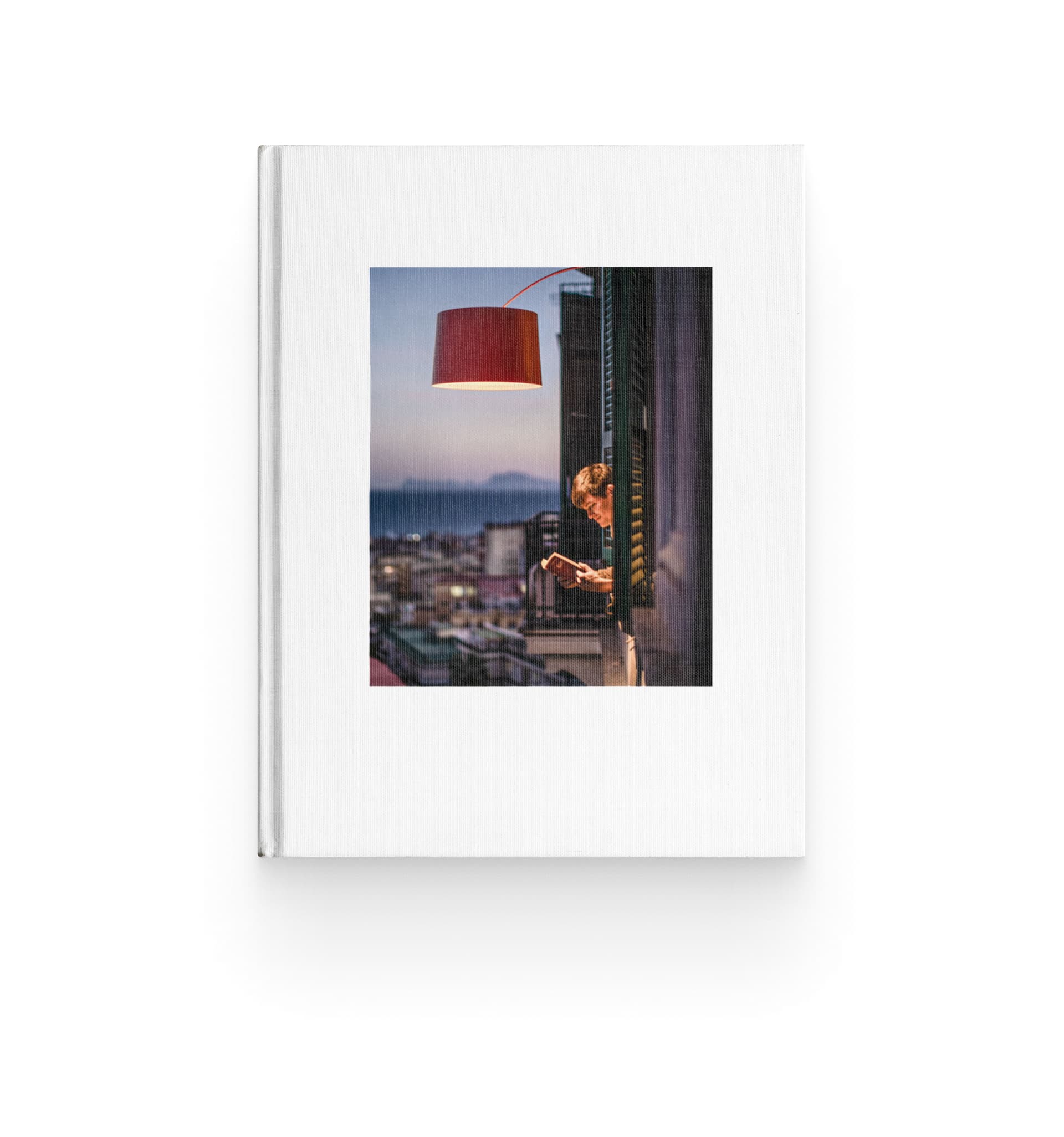

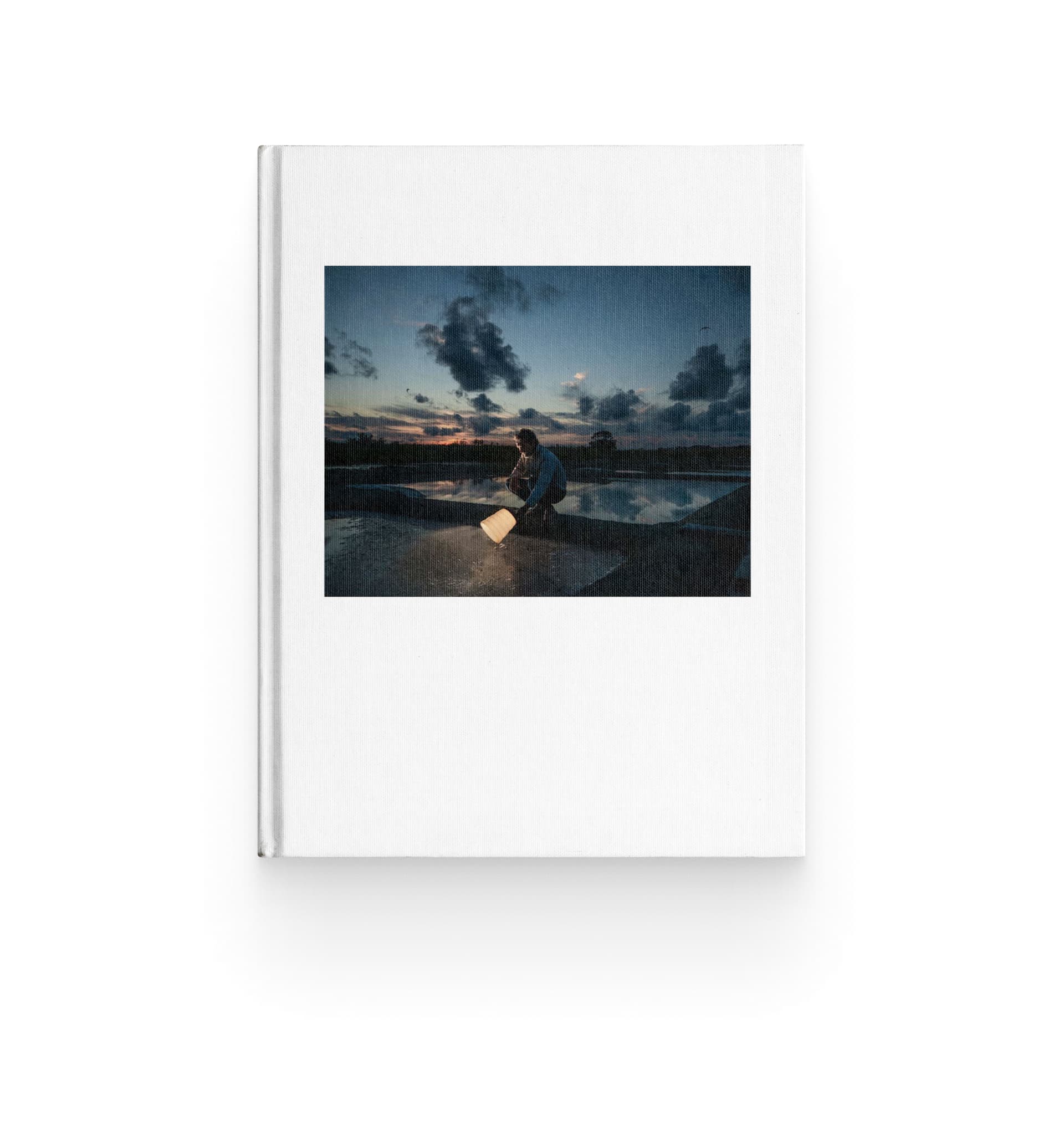

Per What’s in a Lamp?, l’artista torinese Beppe Conti interpreta le lampade non come semplici sorgenti di luce, ma come strumenti che rendono visibile l’invisibile. Nei suoi digital collage, la luce delle lampade Foscarini fa emergere frammenti e strati nascosti, generando spazi onirici e suggestivi.

Beppe Conti è illustratore e visual designer specializzato in collage digitale. Ispirandosi al surrealismo e all’inconscio, fonde elementi organici, visioni astratte e riferimenti tratti da epoche e culture differenti. La sua tecnica è un territorio di libertà che accoglie le contraddizioni e le trasforma in senso. Dove altri linguaggi creativi richiedono coerenza, il collage vive di contrasti e contaminazioni. Negli anni ha realizzato progetti editoriali, branding, mostre e collaborazioni multimediali, producendo immagini capaci di stupire e di far riflettere sul significato profondo delle cose.

Nel progetto What’s in a Lamp?, Conti esplora il dialogo tra luce e ombra. Il buio non è vuoto, ma un campo di possibilità : pattern, gradienti, architetture oniriche e frammenti di realtà emergono unicamente attraverso la luce. L’estetica si ispira alla grafica e alla psichedelia degli anni ’60 e ‘70, in cui il colore diventa vibrazione ed esperienza percettiva.

“Ho immaginato la lampada non come un semplice oggetto che illumina, ma come un dispositivo che genera visioni. Dal buio emergono pattern, gradienti e frammenti di realtà e la luce diventa una forza creatrice, capace di aprire piccoli mondi visivi.”

Beppe Conti

/ artista

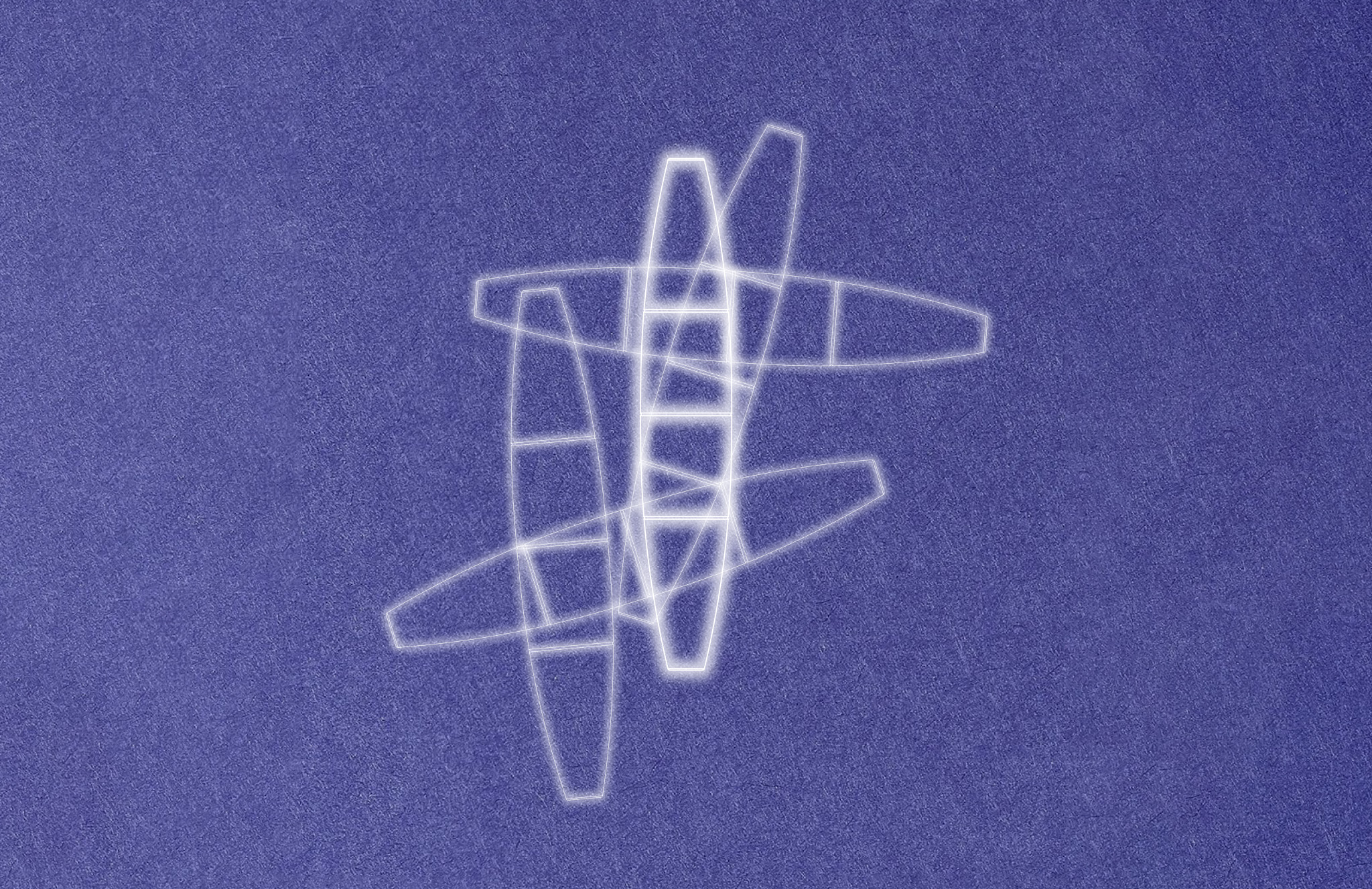

Ogni lampada diventa una storia a sé. Aplomb appare come un elemento architettonico sospeso nel vuoto, dove la luce agisce come forza costruttiva, modellando lo spazio, definendo geometrie ed evocando architetture brutaliste. Dolmen è un monolite ancestrale, un reperto arrivato dallo spazio, che unisce memoria arcaica e immaginazione futurista. Binic, il cui design si ispira al mondo nautico, diventa un micro-faro psichedelico che emerge dall’oscurità, un segnale visivo che non solo illumina, ma segnala e orienta. Anche Gregg, Nile e Tobia trovano nell’universo surreale di Conti nuove, visionarie identità.

Combinando elementi provenienti da epoche e culture, Conti costruisce immagini che vivono nella tensione tra costruzione e decostruzione, tra realtà e immaginazione. Nella serie per Foscarini, le lampade non sono più semplici oggetti, ma metafore di trasformazione: ponti tra luce e ombra, tra terra e cosmo, tra presenza e sogno.

Segui Foscarini su Instagram per scoprire l’intero progetto What’s in a Lamp? e leggere l’intervista completa a Beppe Conti.

Ci racconti il tuo percorso artistico? C’è stato un momento chiave in cui hai capito che l’arte e l’illustrazione sarebbero diventate la tua strada?

Il mio percorso artistico nasce dagli studi in graphic design, che mi hanno dato le basi per ragionare sull’immagine come linguaggio. Poi, con il tempo, si è stratificato, un po’ come accade nei collage che realizzo. Il momento di svolta è arrivato quando ho iniziato a vedere nelle mie composizioni non solo un valore estetico, ma anche un vero e proprio modo di pensare per immagini. È stato lì che ho capito che l’arte e l’illustrazione potevano diventare la mia strada professionale.

Il collage digitale è la tua tecnica distintiva: come sei arrivato a questa forma espressiva e cosa ti permette di fare che altri linguaggi non consentono?

Ci sono arrivato quasi per necessità; cercavo un linguaggio che mi permettesse di unire epoche, stili e materiali diversi senza dovermi limitare a uno solo. Il collage digitale è per me un territorio di libertà che accoglie le contraddizioni e le trasforma in senso. Altri linguaggi chiedono coerenza, il collage invece vive di contrasti e contaminazioni, ed è questo che lo rende unico.

Nei tuoi lavori mescoli riferimenti di epoche e luoghi diversi: hai un tuo archivio visivo o ti affidi soprattutto al caso e alla scoperta?

Uso entrambi. Ho costruito negli anni un archivio di immagini, libri, riviste e fotografie, ed elementi distintivi che rappresentano una base solida. Ma spesso lascio spazio al caso: un’immagine trovata per caso diventa l’innesco di un’intera composizione. Il collage funziona proprio così, nel dialogo continuo tra archivio e scoperta imprevista.

Quanto contano intuizione e casualità rispetto al controllo nel tuo processo creativo?

L’intuizione e la casualità portano freschezza e movimento, il controllo costruisce la forma finale. Lavoro sempre in equilibrio tra abbandono e disciplina: ascolto le immagini, ma poi scelgo, tolgo, ricompongo fino a trovare una giusta tensione.

Quando sai che un’immagine è “finita”?

È un momento intuitivo, non dipende da una regola precisa, ma da una sensazione di equilibrio. È come se l’immagine a un certo punto smettesse di chiedere interventi e iniziasse a respirare da sola. Allora capisco che è conclusa.

I collage che hai creato per il progetto What’s in a Lamp?appaiono onirici e misteriosi, ma nascondono anche un aspetto narrativo. Qual è la storia che hai voluto raccontare unendo il tuo immaginario con le lampade Foscarini?

Ho immaginato la lampada non come un semplice oggetto che illumina, ma come un dispositivo che genera visioni. Dal buio emergono pattern, gradienti e frammenti di realtà che non esisterebbero senza la sua luce. L’estetica guarda molto alla grafica e alla psichedelia degli anni ’70, in cui il colore diventa vibrazione ed esperienza percettiva, un linguaggio ideale per raccontare la luce Foscarini come forza creatrice, capace di aprire piccoli mondi visivi.

Ogni lampada esprime, quindi, un’identità diversa, ma sempre legata al filone luce/buio. Cosa significa per te esplorare questo contrasto?

Luce e buio sono poli opposti ma inseparabili. Nel collage rappresentano la possibilità di costruire e decostruire l’immagine, ma soprattutto parlano di percezione: vediamo solo ciò che emerge da un fondo oscuro. Con Foscarini ho lavorato proprio su questa dialettica, trasformando l’oscurità in una materia viva da cui scaturiscono colori e visioni.

Qual è stata la lampada su cui ti sei sentito più ispirato a lavorare e perché?

Dolmen mi ha ispirato molto per il suo carattere monumentale e ancestrale. La sua forma mi ha permesso di lavorare su immagini archetipiche, quasi rituali, in cui la luce diventa un richiamo a energie primitive, ma tradotte in chiave contemporanea.

Vedi il collage più come un processo di costruzione o di decostruzione?

È entrambe le cose. Costruisco un’immagine nuova decostruendo quelle preesistenti. Il collage vive della tensione tra memoria e invenzione; prendo ciò che già esiste e lo trasformo in qualcosa di inaspettato e nuovo.

Come convivono realtà e immaginazione nel tuo lavoro?

Sono intrecciate. La realtà fornisce i materiali (fotografie, texture, colori ed architetture). L’immaginazione li ricombina in configurazioni nuove. Il collage diventa così una realtà alternativa, fatta di frammenti riconoscibili ma assemblati in un racconto quasi onirico/surreale.

Dentro questo equilibrio, che ruolo hanno la meraviglia e la sorpresa?

La meraviglia è ciò che mi spinge a cercare, a tagliare, a collezionare immagini. La sorpresa arriva quando due elementi lontani trovano improvvisamente un legame; è un momento che non posso controllare del tutto, ed è proprio lì che nasce la vitalità del lavoro.

Per te, che cos’è la creatività?

Per me creatività è la capacità di guardare ciò che già esiste come se fosse nuovo. È un atto di spostamento, di cambio di prospettiva, ribaltare connessioni abituali, mettere in dialogo immagini, tempi e memorie diverse.

Scopri di più sulla collaborazione con Beppe Conti e la serie completa sul canale Instagram @foscarinilamps, ed esplora tutte le opere del progetto What’s in a Lamp?, dove artisti internazionali sono chiamati a interpretare la luce e le lampade Foscarini.